Female genital mutilation in Mali: The fight to end a deadly tradition

Date:

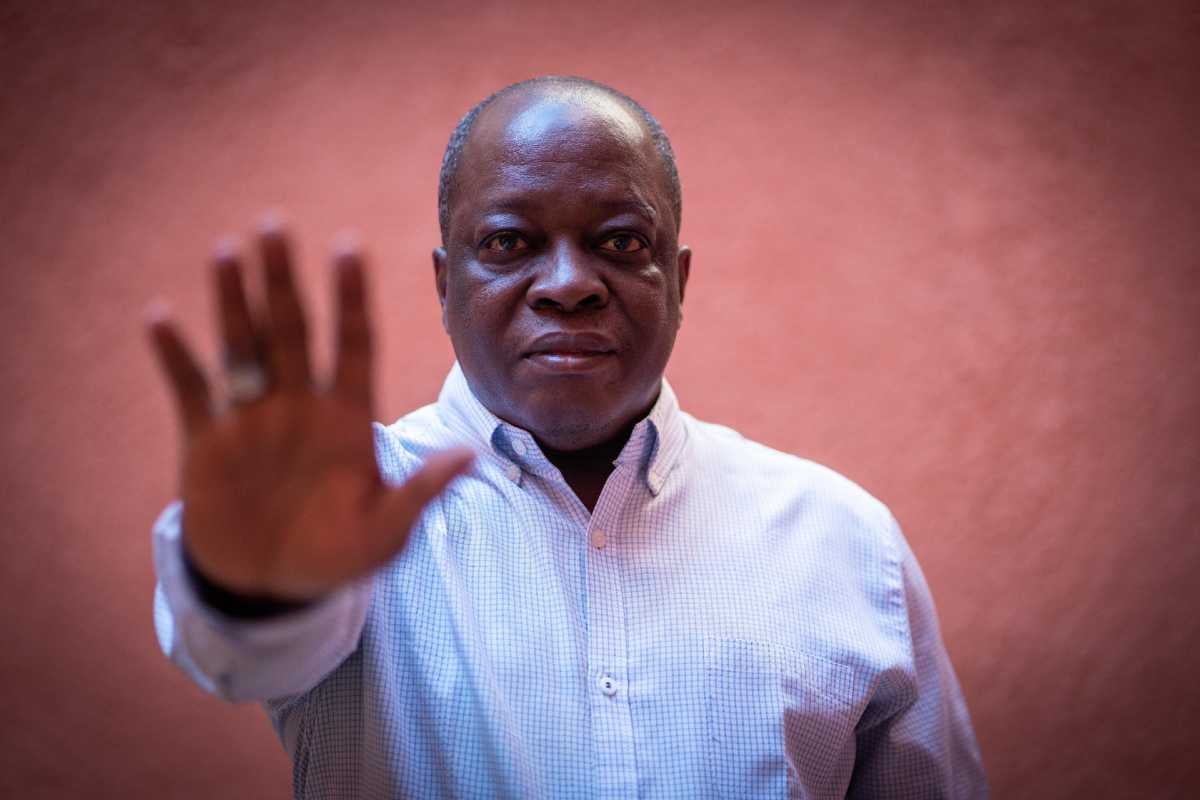

“My mother was an ‘excisor’ and I lived with the practice in my family, believing it was normal. One day, she excised several young girls, and one of them bled to death,” shares Siaka Traoré, whose mother practised female genital mutilation (FGM). Traoré grew up thinking that female genital mutilation was a normal rite of passage for girls in Mali… until that day.

Today, he is a passionate advocate, campaigning to end the practice.

Female genital mutilation: A human rights violation in plain sight

According to official records, 89 per cent of women between the ages of 15 and 49 in Mali have undergone female genital mutilation. Locally, the practice is often referred to as “excision”.

Female genital mutilation is a harmful traditional practice and a form of violence against women and girls. It refers to all procedures involving the partial or total removal of the female external genitalia or other injury to female genital organs for non-medical reasons.

Mali becomes the safe haven for female genital mutilation practitioners

Female genital mutilation is a global problem – every year, more than 2 million girls worldwide experience female genital mutilation, often before their fifth birthday, and sometimes within days of being born.

The practice is most widespread in Africa, where 144 million women and girls have been cut. Many countries are still lacking national laws prohibiting female genital mutilation.

Mali is a case in point, says Traoré, it does not have a national law explicitly prohibiting the practice.

“We asked the Government of Mali to pass a law banning the practice. Since then, we've helped politicians to draw up draft legislation to ban the practice,” shares Traoré, adding that advocates are still waiting for the passage of the law.

In the absence of a law prohibiting it, perpetrators of female genital mutilation enjoy full immunity. What’s more, as neighbouring countries pass legislation to ban female genital mutilation, Mali has made a reputation of being a haven for perpetrators.

“The countries around us, such as Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Guinea and Niger, have passed laws banning the practice. But people leave their countries to come and excise their children here in Mali because we are said to be [female genital mutilation] professionals,” explains Traoré.

“Some people even leave Europe to come and be excised here.”

The consequences of female genital mutilation: A survivor speaks out

There are no health benefits to female genital mutilation. It causes severe physical, emotional, and psychological harm to those affected.

The anonymous testimony of a woman who was unknowingly excised and faced dramatic consequences on her wedding day highlights the silent suffering and shattered lives caused by this practice:

“I was excised, but I never knew that before I got married,” shared a woman from Mali under the condition of anonymity. “My parents married me to a man I didn't know. I was only 15, and on my wedding night, he couldn't have sex with me. He called me a witch and walked out of my life, never to return.”

The woman was among the lucky few who received medical help. While the immediate consequences of female genital mutilation include severe bleeding, infections, and debilitating pain, for many women and girls, it leads to long-term health risks, and even death.

What can be done to stop female genital mutilation

Laws alone cannot stop female genital mutilation. The deeply rooted social and cultural norms driving the practice present a major obstacle. Perceived as an essential rite of passage, questioning female genital mutilation arouses strong resistance within communities.

A whole-of-society approach is needed to prevent and eradicate female genital mutilation which includes enforcing laws, working with traditional and religious leaders, training and sensitizing health professionals, and working with men and boys to reject the practice while empowering girls and women in communities.

A future without female genital mutilation is a better future for all.

FAQs on female genital mutilation

Traumatic. Painful. Irreversible. Learn more about female genital mutilation, its causes, consequences, where it is most practiced, and how global efforts aim to eliminate this harmful tradition affecting millions of women and girls. Read more