FAQs on female genital mutilation

Causes, impact, and how to end it.

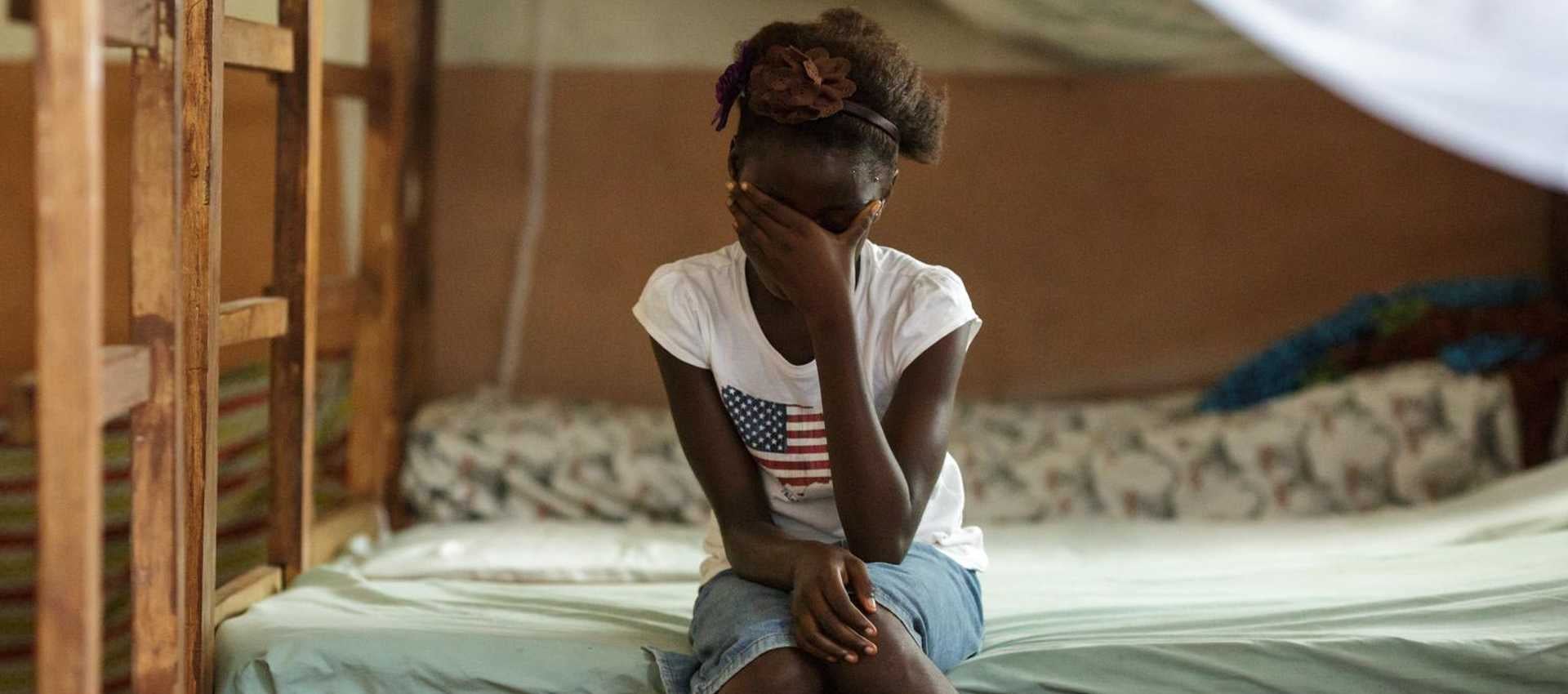

Traumatic. Painful. Irreversible. Female genital mutilation (FGM) is a human rights violation that inflicts lifelong suffering to millions of women and girls. It is a harmful practice that persists because of cultural norms and myths. It has no health benefits, leaving survivors with lifelong physical and psychological trauma.

An estimated 230 million girls and women alive today have undergone female genital mutilation, a number that has risen by 15 per cent – that’s 30 million more cases – over the past eight years.

Alarmingly, more than 2 million girls experience female genital mutilation annually, often before their fifth birthday and sometimes within days of being born.

The increase in number of women and girls experiencing female genital mutilation is due to rapid population growth in regions where the practice is most common, such as sub-Saharan Africa and the Arab States. By 2050, the number of girls born annually in these regions is projected to grow by 62 per cent.

What is female genital mutilation?

Female genital mutilation refers to all procedures involving the partial or total removal of the female external genitalia or other injury to female genital organs for non-medical reasons.

It is also referred to as female circumcision or cutting.

Female genital mutilation is normally carried out between infancy and age 15, although older girls and women may also undergo the practice.

It is most often performed on minors by traditional practitioners, making it a violation of girls’ rights. Female genital mutilation also infringes upon fundamental human rights of girls and women, including their right to health, security, dignity, bodily autonomy and – in cases where the procedure leads to death – the right to life.

Female genital mutilation is classified into four types by the World Health Organization:

- Type 1 (Clitoridectomy): Partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or its surrounding tissue.

- Type 2 (Excision): Partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without removal of the labia majora.

- Type 3 (Infibulation): Narrowing of the vaginal opening by creating a seal, formed by cutting and repositioning the labia.

- Type 4: All other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, such as pricking, piercing, scraping, or cauterizing.

Female genital mutilation is categorized like this to reflect the different types of procedures that are performed and their impact on women and girls. These classifications help researchers, healthcare providers, and policymakers better understand how the practice varies in terms of severity and its health consequences. Regardless of whether it involves smaller cuts or extensive tissue removal, all forms of female genital mutilation inflict excruciating pain, physical and psychological harm, and serious health risks to women and girls.

What are the consequences of female genital mutilation?

Female genital mutilation has no health benefits for girls and women and causes immediate and long-term health consequences.

Immediate sexual and reproductive health issues include severe bleeding, infections, problems urinating, and debilitating pain.

Later in life, girls who have been subject to female genital mutilation face longer-term health risks, such as chronic pain, cysts, abnormal scarring, menstrual problems, sexual problems such as pain during intercourse and decreased satisfaction, infertility, complications in childbirth, postpartum hemorrhages, stillbirth, and increased risk of newborn deaths. In some cases, these complications are fatal to the woman.

The psychological impacts of female genital mutilation include girls losing trust in their caregivers, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and low self-esteem. The physical and psychological consequences of FGM can also become barriers for girls and women to learn, work, and socialize.

Where is female genital mutilation practiced?

Female genital mutilation is a global problem, and is reportedly carried out in 92 countries around the world including diaspora communities. Of those countries, just over half (51) have national laws prohibiting female genital mutilation.

- Africa: Female genital mutilation is reported in 33 countries: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Cote d'Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

- Middle East: The practice occurs in Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Oman, State of Palestine, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen.

- Asia: Female genital mutilation has been documented in India, Indonesia, Malaysia, India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Thailand, Brunei, Singapore, Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos, The Philippines, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and The Maldives.

- Europe: Female genital mutilation has been reported in Georgia, the Russian Federation, and the United Kingdom, often within migrant communities.

- Americas and Oceania: Cases have been identified in the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, as well as in some South American countries like Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, and Peru.

Who is most at risk of female genital mutilation?

UNFPA estimates that more than 4 million girls were at risk of female genital mutilation in 2023.

Although efforts to prevent the practice have led to positive results – with the proportion of girls undergoing female genital mutilation dropping from just over 46 per cent in 1993, to just over 31 per cent in 2023 – population growth in the regions where the practice is prevalent poses significant challenges.

Girls living in poverty and in rural and remote areas are more likely to experience female genital mutilation. The practice is most widespread in Africa, where 144 million women and girls have been cut.

Encouragingly, countries like Cameroon, Ghana and Uganda have already achieved the target of eliminating female genital mutilation before 2030. Benin, the Maldives, Niger and Togo are also on track to achieve zero cases by the end of this decade.

But progress in eliminating female genital mutilation needs to be 27 times faster to meet the global target of elimination by 2030. If the rates of female genital mutilation continue at current levels, 68 million girls will be subjected to it between 2015 and 2030 in the 25 countries where female genital mutilation is routinely practiced.

Why is female genital mutilation practiced?

The reasons behind female genital mutilation vary across regions and communities, often depending on cultural, social, or religious beliefs.

In some communities, female genital mutilation is seen as a rite of passage into womanhood. In others, the practice is used to control a girl’s sexuality or to ensure her "purity" and fidelity for marriage.

Social pressure to “fit in” and the fear of exclusion also play significant roles in keeping the practice alive. In regions where female genital mutilation is widespread, many families see it as crucial for securing a girl’s future, believing it increases a girl’s prospects of marriage and access to inheritance.

In some cases, religious texts are misinterpreted to justify female genital mutilation, despite it not being endorsed by major religions like Islam or Christianity. On the 2024 International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation, the Independent Permanent Human Rights Commission of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation said that Islamic principles and values condemn such practices. The Commission urged countries to adopt strong legal measures to eliminate all harmful practices, including female genital mutilation.

What is the medicalization of female genital mutilation?

The medicalization of female genital mutilation refers to the practice being carried out by healthcare providers instead of traditional practitioners. Two-thirds of all girls who have recently undergone female genital mutilation have been cut by health workers.

Some people mistakenly believe that having the procedure performed by medical professionals reduces the risks associated with it. However, medicalized female genital mutilation still violates human rights and has no health benefits. It reinforces the practice by giving it a false sense of legitimacy and does not eliminate the physical and psychological harm it causes.

Ending female genital mutilation is essential for achieving gender equality, ending all forms of gender-based violence, and empowering women and girls worldwide.

What is being done to stop female genital mutilation?

Efforts to end female genital mutilation include a combination of legislative action, community engagement, and innovative approaches:

- Criminalizing female genital mutilation: Enacting and enforcing laws to ban female genital mutilation is a critical step. However, legislation must be accompanied by strong political will and locally appropriate enforcement mechanisms.

- Healthcare interventions: Female genital mutilation is becoming increasingly medicalized, despite efforts to prevent this. Countries where medicalization is most common are also where the practice is most prevalent, including Egypt, Indonesia, and Sudan. Health workers play a vital role in preventing the medicalization of female genital mutilation and educating communities about its harmful effects.

- Working with traditional and religious leaders: Engaging traditional and faith-based leaders is key to ending female genital mutilation. These leaders hold deep influence in their communities, and when they speak out against the practice, attitudes begin to shift. In West Africa, for example, nearly 9,000 communities have abandoned female genital mutilation through Tostan’s Community Empowerment Program – a movement largely driven by local leaders who champion women’s rights.

- Involvement of men and boys: Men are just as likely as women to oppose the practice in countries where female genital mutilation is active. Some 200 million boys and men living in practicing countries in Africa and the Middle East think female genital mutilation should stop. Approximately 70 per cent of couples worldwide with at least one daughter aged 14 or under want the practice to end. Men, as influential members of their communities, can help challenge societal norms and advocate for ending female genital mutilation.

- Funding to end FGM: By the end of the decade, an estimated $275 million will have been spent on addressing female genital mutilation; however, $2.4 billion is needed to reach the goal of eliminating the practice in 31 high-prevalence countries by 2030. Funding for programmes to end female genital mutilation has decreased considerably in recent years, especially for women’s organizations and survivor-led movements.

- International cooperation: Strengthening legal frameworks to address cross-border and transnational practices of female genital mutilation and harmonizing efforts across countries is essential for its elimination. The United Nations has played a pivotal role in global efforts to end female genital mutilation using resolutions that have consistently called for the end of all harmful practices against women and girls, including female genital mutilation. In 2024, the European Parliament adopted a new directive forcing all European Union countries to criminalize female genital mutilation, increase awareness of the practice, and provide support to survivors.

What is UN Women doing to end female genital mutilation?

UN Women works on multiple fronts to end female genital mutilation, from advocacy and policy change to grassroots action. UN Women is also the penholder of the Secretary-General's Report on Female Genital Mutilation, which captures the latest data, challenges, and progress to drive global action to end the practice.

One key initiative is the ACT (Advocacy, Coalition-Building, and Transformative Feminist Action) to End Violence Against Women programme, a 22-million-euro collaboration with the European Union. This initiative focuses on advocacy, coalition-building, and addressing harmful practices, particularly in Africa.

UN Women participates in a taskforce alongside the UN Development Coordination Office, UN Devlopment Programme, UN Trust Fund to End Violence against Women, UNICEF, OHCHR, and WHO to coordinate efforts to eliminate female genital mutilation worldwide.

UN Women also supports real change on the ground:

- The Gambia: When attempts were made to repeal the country’s female genital cutting ban, UN Women stepped in to activate human rights mechanisms, work with civil society, and mediate expert dialogues with women’s rights organizations, activists, and UN partners. These discussions boosted efforts to uphold the law and push back against attacks on women’s rights.

- Somalia: With support from the UNTF, grassroots organizations in Somaliland led efforts to shift deep-seated beliefs about female genital mutilation. Through education, dialogue, and community engagement, these efforts led to a remarkable transformation with parental support for ending the practice surging from 72 per cent to 100 per cent, and the number of religious leaders recognizing its harmful effects rocketing from 52 per cent to 96 per cent.

- Liberia: Through the Spotlight Initiative, UN Women and partners worked with the National Traditional Council of Chiefs and Elders to extend a national ban on female genital mutilation for another three years. The project also helped 300 traditional practitioners transition to new livelihoods, providing training in climate-smart agriculture and other economic empowerment opportunities.

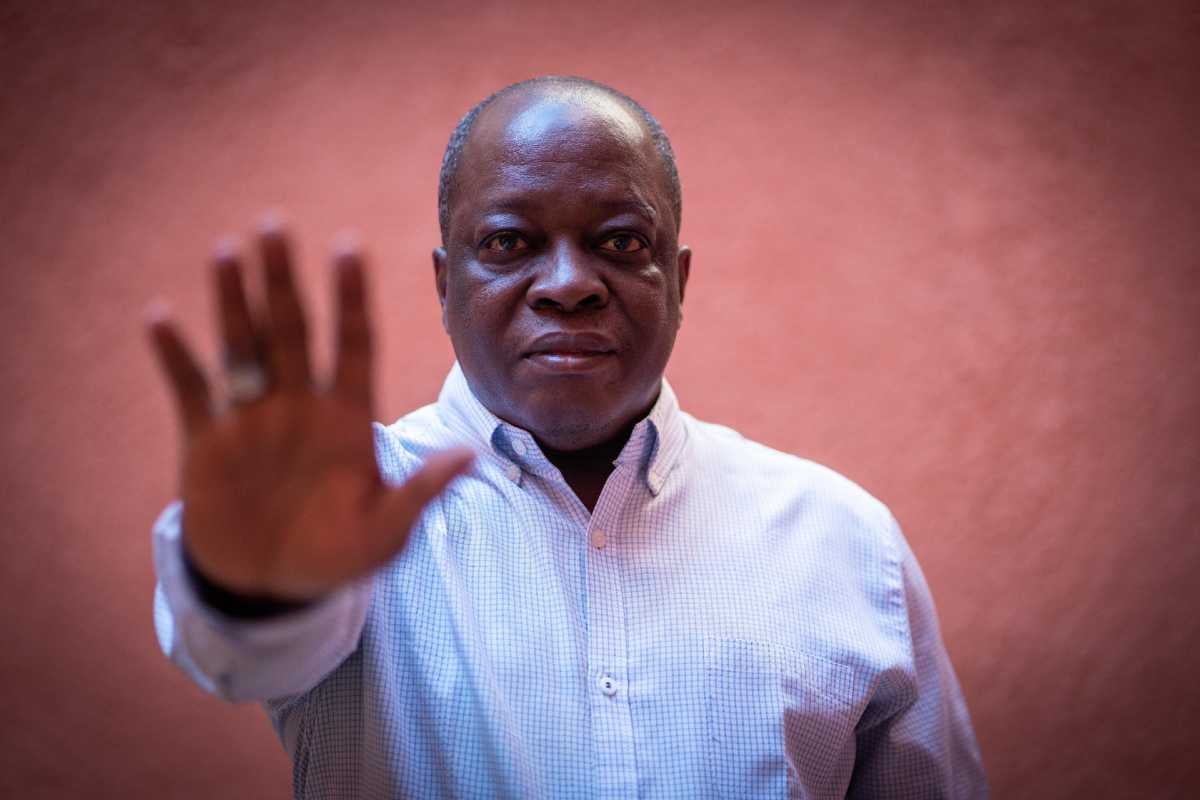

The fight to end a deadly tradition

In Mali, where 89 per cent of women have undergone female genital mutilation, advocates like Siaka Traoré are fighting to end this deadly tradition. With no national law banning the practice, Mali has become a safe haven for the practice, drawing families from neighboring countries and even Europe. Survivors speak out about the devastating consequences, while activists push for legal and cultural change. Read more